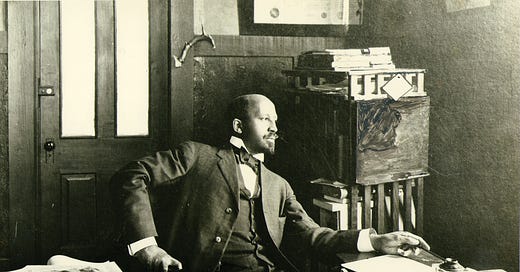

W.E.B Du Bois: A Defender of the Tradition

A Defense of Liberal Education in the "The Talented Tenth"

“The function of the university is not simply to teach breadwinning, or to furnish teachers for the public schools, or to be a center of polite society; it is, above all, to be the organ of that fine adjustment between real life and the growing knowledge of life, an adjustment which forms the secret of civilization.”

― W.E.B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk

W.E.B Du Bois was born in 1863 and led an academic life. He was the first African American to receive a PhD in the history of America, accepting it from Harvard. Du Bois had an academic personality and tended to find his home in the northern United States, both ideologically and personally.

Du Bois believed in a liberal education. Du Bois studied at an Ivy League institution and university in Germany. Due to this, Du Bois was steeped in the tradition of liberal education. Yet, what purpose does this liberal education serve?

Du Bois wrote an essay titled, “The Talented Tenth,” arguably his most known work. One of the goals of this small but powerful essay was an attempt to validate a liberal education. Du Bois is traditionally set apart from the educational philosophy and ideas of Booker T. Washington. Washington advocated for manual training or a skills-based education. Du Bois was not opposed to this, but Du Bois saw a higher purpose in education. He writes,

“But this is true: A university is a human invention for the transmission of knowledge and culture from generation to generation, through the training of quick minds and pure hearts, and for this work no other human invention will suffice, not even trade or industrial schools.”1

Du Bois is not necessarily opposed to manual training itself, rather, that a skills-based education is not the proper end of the education needed. He writes,

“Nevertheless, I insist that the object of all true education is not to make men carpenters, it is to make carpenters men; there are two means of making the carpenter a man, each equally important: the first is to give the group and community in which he works, liberally trained teachers and leaders to teach him and his family what life means.”2

Du Bois turns back to the famous abolitionist, the men who led the emancipation of the black community in America. Du Bois wants to ground the necessity and importance of a liberal education in history, calling his community to see the validity of education as a form of emancipation. Unsurprisingly, it was a challenge to convince his community that a liberal education could offer the potential to free them. He writes in “The Talented Tenth,”

“Where were these black abolitionists trained? Some, like Frederick Douglas, were self-trained, but yet liberally; others, like Alexander Crummell and McCune Smith, graduated from famous foreign universities. Most of them rose up through the colored schools of New York and Philadelphia and Boston, taught by the college-bred men like Russworm, of Dartmouth, and college-bred white men like Neau and Benezet.”3

Clearly, Du Bois is attempting to ground the necessity of education in the past, yet striving for particularly liberal or university training.

Du Bois believed that a good teacher must be a leader for the black community. Du Bois is fighting against the bureaucracy that was making it extremely difficult for the black community to become teachers, and thus for their children to be educated. Du Bois saw the teacher's role as one that is vital. Our modern belief in the ability of education as a form of cultural emancipation is due to these very ideas of Du Bois. He wanted to free his community and have them synthesize into the broader American context. Sure, having a strong economic force —the likes Booker proposed—would help, but for man to be truly free, he must stand on something much stronger than skills. The black community must have liberally trained teachers to go back to their own communities and offer this education to the youth. He must stand upon the sure footing that a liberal education grants.

These teachers that Du Bois was advocating on behalf of, would be the leaders of this communal uplift, offering a form of cultural emancipation. Du Bois eloquently concludes the “Talented Tenth” by writing,

“Education and work are the levers to uplift people. Work alone will not do it unless inspired by the right ideals and guided by intelligence. Education must not simply teach work – it must teach Life. The Talented Tenth of the Negro race must be made leaders of thought and missionaries of culture among their people. No others can do this work and Negro colleges must train men for it. The Negro race, like all other races, is going to be saved by its exceptional men.”4

Through the education the liberal arts have to offer, coupled with strong teachers as leaders, a healthy synthesis can be achieved. Thanks to thinkers like Du Bois, we now live in a world that desires a fair education for all. Regardless of whether one sees liberal education, as Du Bois did, or any other form of education as proper, we all can agree that the debate over education is necessary now more than ever. Du Bois and many thinkers after him have proved that the value of a good education is not something to be taken lightly. Even though Du Bois was speaking to his particular community, that does not invalidate his ideas. A good education is necessary for all, regardless of birth, color of one skin, or religion. I will leave you to sit in the beauty of his prose,

“I sit with Shakespeare and he winces not. Across the color line I move arm in arm with Balzac and Dumas, where smiling men and welcoming women glide in gilded halls. From out the caves of evening that swing between the strong-limbed earth and the tracery of the stars, I summon Aristotle and Aurelius and what soul I will, and they come all graciously with no scorn nor condescension.”5

Perhaps, just as Du Bois dreamed, we ought to return to a liberal education that he so resilient advocated.

-D.R.L

Bois, W.E.B Du. “The Talented Tenth.” 5.

Du Bois, “The Talented Tenth.” 13.

Du Bois, “The Talented Tenth.” 3-4.

Du Bois, “The Talented Tenth.” 17.

Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk. 88-89.