Medieval Grammar and the Classical Classroom

A Study of Medieval Pedagogy

Modern educationists have pushed back in recent years against common vernacular instruction in the classroom.1 In the past years, educators–public and private alike–have seen a sufficient decline in students’ ability to write proficiently.2 This comes as no surprise when public education has called for an abandonment of formal grammar instruction in the K-12 classroom.3 Unsurprisingly, higher education professors have spoken out about students’ inability to communicate their thoughts well in writing.4 Yet, in the contemporary classical education movement, the teaching of formal grammar is still seen as not only necessary but also fruitful in the movement’s hope to offer a well-rounded education.

For the sake of this article, I ask my readers to grant me an oversimplification of language instruction in contemporary classical education. Contemporary classical education sees itself as recovering many lost arts in education. In the classical education movement, we see various strands of recovery: a return to liberal arts, humane letters, Latin, classical approaches to science and natural philosophy, and many other disciplines, but there is a lack of understanding on how to recover the teaching of grammar.

It appears that Latin and English grammar instruction are deemed as two entirely separate tasks in contemporary classical education. On the one hand, we have the study of English grammar. This instruction starts in the early grades and functions very similarly to that of modern progressive grammar instruction. This instruction is centrally focused on things such as proper punctuation, spelling, and good syntax. On the other hand, there is Latin instruction. Latin instruction starts in a variety of grades yet is always seen as separate from vernacular instruction. Latin instruction consists of learning all the parts of speech, grammar, and language constructions that consist in the learning of a new language. Traditionally, Latin instruction’s goal is translation of some kind, reaching its fruition in a variety of ways, but normally with a reading by Cicero or Virgil. Even though both vernacular instruction and Latin instruction may seem like two entirely separate subjects, this article believes that both Latin and English instruction ought to be taught in conjunction with each other. Not only should they be held in conjunction with each other, but this paper believes that using medieval grammar pedagogy can help recover a more traditional approach to grammar instruction. The contemporary classical education movement would find a particular reward in deepening its understanding of what grammar instruction has looked like in the past. Not only would a reward be granted for casting our eyes to the past, but also by recognizing the potential that medieval grammar pedagogy has in the classical education movement. Strength in the vernacular language should always be the primary goal, yet using Latin instruction, writing, and a medieval approach to grammar to strengthen the vernacular should be considered.

It is important to note the place of formal writing instruction. As previously mentioned, grammar instruction–in its modern context–exists as a set of skills or a series of abstract rules to learn and subsequently follow. In modern education, writing and grammar instruction are rarely taught hand in hand, yet traditionally, both disciplines were seen as all part of a single activity: strength in language. Before examining medieval grammar, it is important to note the robust relationship both grammar and writing instruction had in the past.5 Each of these skills was seen as the same endeavor. Grammar and writing instruction both had the same end: creating a strong mind through grammar, logic, and rhetorical instruction. Through this article, grammar and writing instruction should be seen as tightly bound activities.

When speaking of medieval grammar,6 this article is referring to specifically monastic grammar. In the 12th century, the study of “grammar” was a lot broader than the modern understanding of grammar. The monastic study of grammar was the first on a medieval curriculum, subsequently followed by a study of Logic and Rhetoric. The function of grammar in the 12th century was seen as foundational to all subsequent studies.7 One keynote about monastic grammar is the primacy of Latin. Within monastic education, Latin was the sole language in which all instruction, writing, and memory were done.

What was grammar pedagogy in the 12th century? In the book titled Medieval Literary Theory and Criticism c.1100-c.1375: The Commentary Tradition, A.J Minis and A.B. Scott discuss this very topic. They write, “Grammar is not simply a matter of learning how to write and speak well, declared Thierry of Chartres…echoing a long-established definition: it also has its proper task the explanation and study of all the authors.”8 There are three separate grammar activities this article will examine. The three parts of grammar instruction in the 12th century were introduction to the authors, commentary of the texts, and copying.9 Jean Leclercq explains the function of this tri-part division in his book The Love of Learning and the Desire for God. Leclercq explains how all three of these pedagogical steps offered the monastic student the ability to gain strength in language.

The first step in grammar instruction was an introduction to the authors. This first step was a close study of the auctores. Leclercq writes, “Who are these auctores?... In brief, the scholastici (or auctores) are all the ancient authors who can serve as guides to good expression, the first step in good thinking.”10 The authors studied in the “Introduction to the Authors” depended on the monastic institution and its leaders, but certain writers tend to appear more than others. A few examples, among others, are Donatus’ Ars Maior, Priscian’s Instutiones, Quintillains’ Institutio Oratoria, and Horace’s Ars Poetica.11 It is important to note that these were the canon writers of the monastic era. These monastic teachers led their students through a rigorous study of grammar using the past authors as models.

Leclercq writes, “No author was taken up without preparation. This introduction was effected through preparatory notes on each which were called accessus ad auctores.”12 Before formal grammar instruction began, medieval students would immerse themselves in the study of past authors. This immersion consisted of a variety of questions posed about the author or work. These questions would be asked on account of the work for the students to be forced to engage with the text on a deeper level than surface reading. Leclercq makes this explicit when he writes, “The accesses is a short history which takes up for each author the following questions: the life of the author, title of the work, the writer’s intention, the subject of the book, the usefulness of its contents, and finally, the questions what branch of philosophy it belongs to.”13 Once an adequate introduction had been done, the student moved on to “commentary of the texts.”

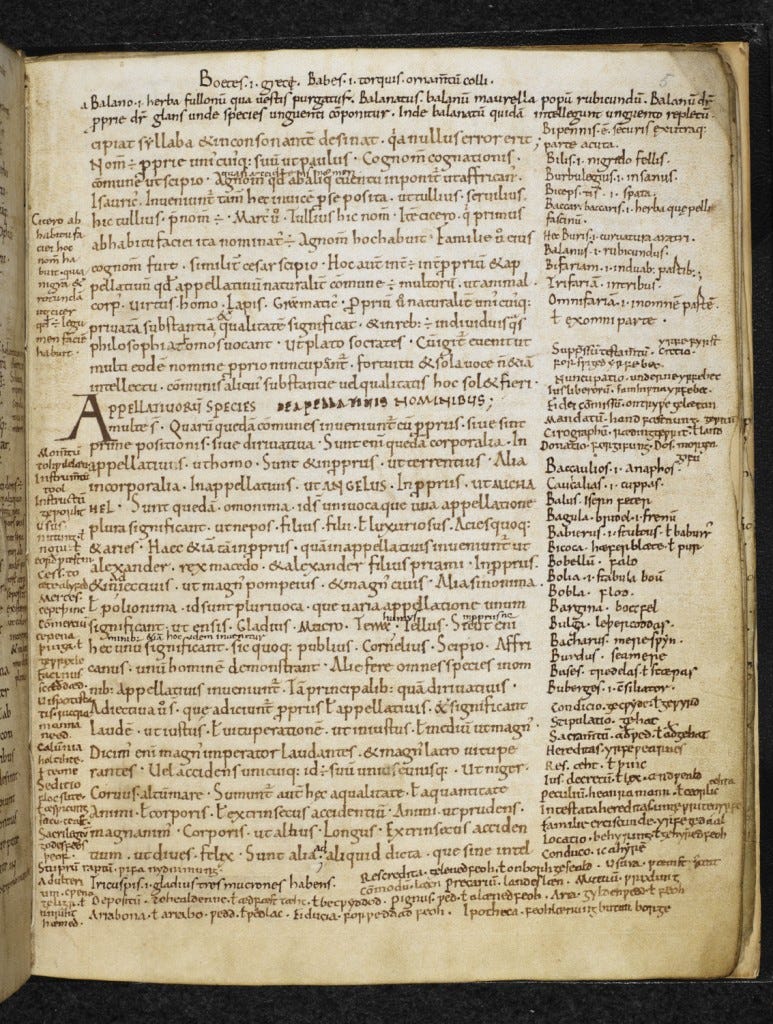

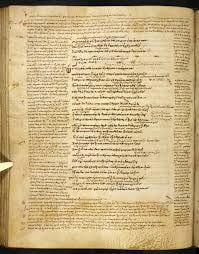

These commentaries functioned as minute observations of a singular text. As previously stated, the introduction to the authors functioned as a broader and more general observation of these texts. The commentary or glosses was an intricate study of each word in a text. The medieval teacher thought that through a close examination of texts, line-by-line examination, the beauty and skill of an author could be made more evident. Leclercq writes, “While the accessus was a general introduction to each author and to each work, the gloss is a special examination of each word in its text.”14 Again, he writes, “To look for and find in this way an equivalent for each word necessitates acquiring not only a general idea of the work through a superficial reading, but a minute, attentive study of all the details. The superior wisdom sought for in these texts is obtained only through grammatica. No doubt this procedure was not practiced everywhere or always in the same manner and to the same degree, but it is attested by manuscripts of every period: it was, therefore, a constant of medieval education."15 This commentary of the text offered to its pupils a detailed study that brought forth the worth, skill, and talent needed to produce works of this caliber. Only through such minute observations could a text be shown as a truly great work.

Lastly is the study of “copying.” Traditionally, when one thinks of copying, one thinks of writing down the exact words as they appear on the page. Yet in the monasteries, copying had a different function. In the days of poorly constructed and preserved manuscripts, the task of the copier was not only difficult but also one that was honored. For the sake of this paper, the main point to be gleaned from the task of the copier is the task of revision. The medieval scribe is not copying down the exact words as they appear on the page. Rather, he must do two things. Firstly, he had to decipher what was on the page and make a judgment. Due to the lack of ability to properly preserve manuscripts in the medieval era, the scribe had to make editorial decisions. He must decipher what he can read on the page and decide what to write down. Secondly, he would make revisions or adaptations to the work. Leclercq writes, “Each text transcribed required very careful revision, correction, collation, and criticism.”16 To the modern reader, this clear abandonment of authorship may be surprising or ever deemed wrong; yet, to the medieval scribe, his role was one of participating and carrying on the tradition of reading these great texts.17 Thus, making revisions and adaptations of these auctors was seen as the job of the scribe. A wise reader will set aside the modern question of authorship for a more friendly conception of medieval “copying.”

The examination of these three activities, namely introduction to the authors, commentaries, and copying, all can be used in the modern classroom. A teacher should not strive for direct imitation of these monastic pedagogical practices; rather, educators should use these past practices as guides for their classrooms and schools. One should not expect their students to be doing the acessus ad auctores in fluent Latin, but we could use some of these medieval practices in vernacular language instruction. For example, a teacher could take a passage from Milton or Shakespeare and ask their students to diagram the sentences within the passage. Then, the teacher could ask them to list all the parts of speech in the passage. Then, ask the students to list a synonym for every word in the quote. Their homework could be choosing three words that Shakespeare used and writing a paragraph defending why Shakespeare's words are better than their listed synonym. This type of practice can truly open our eyes to the possibility of well-rounded grammar instruction that is steeped in the past. This pedagogical practice does not have to just stay in Grammar or Literature class. A Latin teacher could take a passage from Virgil and do the same. It is my hope in the coming years that the classical education movement starts to look to the past for pedagogical practices. Yes, many attributes and skills of a teacher do not change as time moves on, but if classical education truly believes in recovering lost arts, then it also needs to look at recovering pedagogical practices.

-D.R.L

Missy Watson. “Contesting Standardized English.” AAUP.org, May-June 2018: “But Let Us Cultivate our Garden,” https://www.aaup.org/article/contesting-standardized-english.

826 National Publication. “The Truth About Writing Education in America: Part Two.” 826national.org, June 2022, https://826national.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Full-Report_Truth-About-Writing-Education-in-America_Part-2_Raising-Teachers-Voices.pdf

National Council of Teachers of English. “Position Statement: Resolution on Grammar Exercises to Teach Speaking and Writing.” NCTE.org, November 30, 1985, https://ncte.org/statement/grammarexercises/

Michael J. Carter and Heather Harper. "Student Writing: Strategies to Reverse Ongoing Decline: AQ." Academic Questions 26, no. 3 (09, 2013): 285-295. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/student-writing-strategies-reverse-ongoing/docview/1433067292/se-2.

The seminal source on this topic is the monumental work by Rita Coupland and Ineke Sluiter titled Medieval Grammar and Rhetoric: Language Arts and Literary Theory, AD 300-1475. This encyclopedic work stands as the best source to date on Grammar and Rhetoric instruction in the medieval world.

There has been much debate about when the “medieval era” began. Though this is an interesting question, this paper will be specifically looking at the 12th-century accounts of writing instruction. This paper will assume that the 12thcentury is in the Middle Ages. Thus, whenever “medieval” is stated, our readers know that the 12th century is assumed.

Although not on monastic education specifically, there is a fantastic book on 12th century schools titled A Companion to Twelfth-Century Schools, edited by Cédric Giraud. Not only is this book a great secondary source, but it also has a great chapter titled “Methods and Tools of Learning.” This chapter offers a couple of practical pedagogical techniques used in schools from this era.

A.J Minnies and A.B. Scott, Medieval Literary Theory and Criticism c.1100-c.1375: The Commentary Tradition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), 12.

Jean Leclercq, The Love of Learning and the Desire for God (NY: Fordham University Press, 1961), 115.

Leclercq, The Love of Learning and the Desire for God, 114.

Many of these primary sources are in the seminal work Medieval Grammar and Rhetoric, edited by Rita Copeland. Section Four, titled “Pedagogies of Grammar and Rhetoric, ca. 1150-1280,” is particularly helpful in engaging with these primary texts.

Leclercq, The Love of Learning and the Desire for God, 115.

Ibid, 116

bid, 120.

Ibid, 120.

Ibid, 122.

The book Medieval Theory of Authorship: Scholastic Literary Attitudes in the Later Middle Ages by Alastair Minnis is a great book on this topic.